May – August, 1981

“Newspapers: you’ll never be able to carry your video display terminal on the subway. You’ll never be able to take it in the bathroom and sit on the toilet and look at it. You’ll never be able to set it on your kitchen table and look at it and read it. Newspapers aren’t dead. Ted Turner be damned. It’s a bizarre, absurd and outrageous thought.”

-ThroTTle co-founder and Editor Peter Blake, in a 1982 interview

Give Peter a break, he was a magazine Editor, not a fortune teller.

Then again, in 1982 an unknown cartoonist named Matt Groening sent Brumfield a badly-drawn comic called "Life in Hell", about these rabbits. Dale sent it back, deeming it too amateurish. As everyone knows, Groening went on to create "Futurama".

Then again, in 1982 an unknown cartoonist named Matt Groening sent Brumfield a badly-drawn comic called "Life in Hell", about these rabbits. Dale sent it back, deeming it too amateurish. As everyone knows, Groening went on to create "Futurama".

Volume 1, No. 2 of ThroTTle magazine was a hit. All 1,000 copies were scooped up as fast as they were distributed, making it possibly more rare than number 1. By April of 1981 the magazine was getting noticed: more and more frustrated writers and artists were contacting the staff, eager to latch onto what they may have perceived as the next big thing.

The situation surrounding the inception of ThroTTle is quite remarkable. One of the largest, most prestigious art schools in the world was right in Richmond yet there was no regular outlet for publishing the artists’ works. VCU also had a booming creative writing department, a huge Mass Communications department and a fast-growing film and photography school, yet there was not one publication in that entire city that catered to those talents, other than the CT. Richmond’s rock and roll and alternative music scene was jumping, and the bands had no way to promote themselves or advertise their shows other than on utility poles. Like most successful venues, ThroTTle was the confluence of several perfect storms at precisely the right moment.

Interest in the magazine was high, and letters to the Editor rolled in, responding to the first two issues. A person identified as “Young Pamunkey” had plenty to say about Jack Moore’s controversial article on the Pamunkey tribe in issue #2: “Me see your story. Misquote my people, twist words. Me think you asshole.” It started.

Someone claiming to be from Camp LeJune wrote a head-scratching letter about long snakes. A VCU Mass Communications major named Stephen Arnold wrote in, claiming ThroTTle did a “fine job of making me laugh”.

Then they got a letter from Ron Smith.

Dale Brumfield and Bill Pahnelas had met Ron the previous year when the band “Dickie Disgusting and the Degenerate Blind Boys” exploded on the Richmond punk scene. Ron was the Blind Boys’ manager/PR guy/pharmaceutical expert, and made incredible flyers for the band with literally no technological assistance.

Ron had dubious contacts around town. He claimed to know a guy from a dentist office that could hook them up with nitrous oxide. “Do you want some gas?” Ron claimed the guy would say if they knocked on his door exactly 4 times and told him Ron sent them.

Ron claimed somebody he knew got a tank and spent labor Day weekend on his couch with the mask over his face in a constant state of willingness to get every tooth in his head pulled.

Impressed with Ron’s artistic prowess, Dale actually let him design the cover of the Commonwealth Times “Sun of Summer Issue” in August, 1980 (seen on the home page of the Commonwealth Times digital library at the VCU website linked on this page). Ron was a kid in a candy shop, suddenly with stat cameras and typesetting equipment at his disposal as he showed up in his skinny jeans, black & white striped shirt, flip-flops, frizzy hair and wraparound sunglasses to create his cover art.

After the 1980-81 school year started Ron (and the Blind Boys) vanished, only to reappear, pissed off as usual and angry as hell at ThroTTle (punctuation and capitalization remain as is):

“Dear sterile, unflavored, LIMP kitty box liner manufacturers,” the letter began. “Where’s some style!! Some real content!. . .What’s with BILL and JACK? . . .I MEAN hanging out in west point, drinking beer and “reflecting”, & LIFE IN THE WEST END with BANK HERMIT & CATS???? Common you guys you’re SLIPPING. JEEZUZ. . .”

While most of the staff dismissed the letter as addled ramblings, Peter and Bill – perhaps jolted by his harsh rebukes – responded to it as they knew best. They called Ron and hired him to write a column.

That was typical of the style of participation Peter advocated for the magazine. Peter was very good at listening to criticism and had a natural way of filtering out the BS and retaining what mattered. Peter’s style this way was critical to the success of the magazine, and was an excellent way of bringing in talent that otherwise would never have been found. It was turning shit into shinola, and Peter was the master of it. Ron showed up that April, eager to help out and astonished he was asked to participate in light of his criticisms. He remained an important part of the magazine for years, and his unflinching stories on a Klan rally in Bowling Green and his columns on the music scene generated more mail and controversy than any other features. Love Ron’s stuff or hate it, the guy could generate conversation.

“We’ve had some problems, particularly with bands,” Bill explained in a 1982 interview. “People who don’t like what Ron [Smith] writes, people who ask why we let him write that. For the people who do write regular columns, we don’t tell them what to write. We let them use their own judgment, and that’s what makes our magazine what it is.”

In other words, if you want to be edited, go to the Times-Dispatch.

While there were divergent views from all the core staff people on what the magazine was becoming, nobody was interested in recruiting people to write for them then tell them sorry, we won’t print your piece because it isn’t what we wanted to see. It was the desire to include as many voices as possible, as again, ThroTTle was the only game in town in the Spring of 1981. If you don’t like what you see, the magazine was saying, don’t go away - send us your stuff.

Since letters and submissions were rolling in, the staff felt they were now obligated to keep publishing. As Bill said, “We’ve allowed events to take us where they would . . . it’s basically gone the way I thought it would. We’re creating a forum, a marketplace for ideas and an audience. As time goes on we’re seeing the manifestation of all those things in the magazine. Not so much as a conscious effort, but as a gathering of momentum.”

Around the first week of May of that year, work began on Volume 1, number 3 of ThroTTle. A lot was happening, both regionally and nationally, that begged for some sort of ThroTTle treatment. Statewide, Prince Charles arrived in Williamsburg May 2 to accept an honorary fellowship at William and Mary. Washington Post journalist Janet Cooke had been stripped of her Pulitzer when she admitted she made up her story “Jimmy’s World”, about a supposed 8-year-old heroin addict.

|

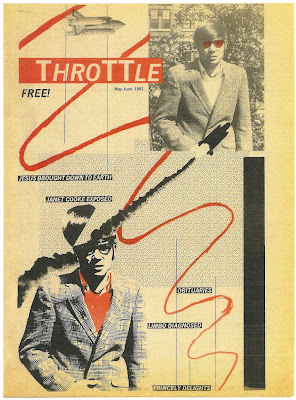

| ThroTTle cover, Vol 1 No. 3 |

Richmond lost two landmarks that Spring: the original Village restaurant at Grace and Harrison closed after a 23-year run (remember the upside down serving trays on the ceiling?) and the Sears Roebuck at 1700 West Broad Street closed after serving Richmond since 1947 at that location.

Facing a glut of story ideas, the Editors met in two separate meetings to filter through the submissions and select enough to fill another 12-page issue (although they had enough material for an issue twice that size).

Once the stories and art work were selected, Dale decided to try a different idea for the magazine’s layout: rather than design the entire magazine himself, he would do just the cover, then recruit several people to try their hand at their own page layouts. He saw page design just as legitimate an art form as art or photography, and would involve still more members of the art community in the construction of the magazine.

“The offices resemble those of psychopathic mass killers . . .”

VCU had inadvertently become a bigger part of that May/June, 1981 issue of ThroTTle than they ever intended, in particular the student activities office and activities director Ken Ender.

Ken (known affectionately by the CT and ThroTTle as “the Beav”) was a hell of a nice guy but got entangled in a controversy regarding a flyer created by a couple of ThroTTle staffers for a fictitious band called “Manley Vigor and the Large Men” that got stapled to phone poles in and around the VCU area. The art and design of the flyer looked suspiciously like a recent student activities calendar produced by the same couple of guys, so people (especially some local feminists and gay rights activists) who took outrage at the Manley Vigor flyers assumed wrongly they were sanctioned by the VCU student activities office.

The problem with the flyer is that one of the creators cut a partial headline out of a tabloid and pasted it on the flyer as an afterthought. The original headline, from the Washington City paper, read “Publisher Moves to Kill Modern Womens Magazines”, but the headline got ripped in the waxer, and the part that made it on the flyer said only “Kill Modern Women”.

(Sidebar: a headline from the Baltimore Sun Op-Ed page that said “Mush from the Wimp” and was never meant to go into publication was also destroyed in the same waxer incident.)

To add injury to insult, a registration mark (made famous recently by Sarah Palin as “targeting” congresspeople to be voted out of office) appeared directly on the rear end of a male basketball player on the flyer. A Richmond homosexual advocacy group joined in the fray, saying that a gun sight on the guy’s butt was in fact an invitation to encourage violence against gays.

The fallout was immediate and very harsh. VCU released a press release announcing they were in no way connected with the flyer or the event, which was advertised at the university library on a day the library was closed. President Edmund Ackell was forced to respond to a complaint, an activity he found most unsavory. Student Activities Dean Phyllis Mable sided with the two creators, realizing the controversy was completely unintentional and that the detractors were acting less out of concern for their own well-being but more out of a hysterical desire to focus attention on their organizations and causes.

Talk at the Times-Dispatch newsroom of a “controversy” at VCU never materialized into a story. The President of the local chapter of an early version of NOW visited the ThroTTle (also Commonwealth Times) offices in an attempt to confront the flyer creators and reported back to President Ackell that the graffiti made the offices “. . .resemble those of psychopathic mass killers.”

Her frame of reference to this day remains suspect.

The two people behind the flyer (remaining nameless) were stunned by how quickly the situation blew out of hand, but were immediately apologetic, and sent written apologies to Ken Ender and the student activities office regretting implicating them in the controversy. While a few of the more strident feminists demanded the two students be expelled, cooler heads prevailed and the controversy soon died.

But to celebrate the staff members’ exoneration, Dale elected to honor Ken Ender and his role in helping squash the controversy by putting a 1969 picture of him (actually 2 of them) on the cover of ThroTTle #3. The illustration shows the top of his head opening up Terry Gilliam-style and a Charles Sugg photo of a space shuttle blasting off out of it, landing in a rather embarrassing spot in the upper picture.

Another new element added to issue #3 was spot color. Peter struck a deal with the Herald-Progress regarding color: If the press was already set up with a spot color for the daily paper, ThroTTle could use it and only be charged for an extra plate. The magazine then went to the printer with a color separation without knowing what color it would be until it came off the press. For issue 3 red came out. While the feminists may claim it represented blood it was in truth a happy accident, highlighting the ThroTTle logo on the cover and design elements on the back page, a piece of fiction titled “A Barber Shop Story” by David Keller and designed in a stunning punk style by local artist Jim Nuttle, who had been turned away at the door of a 42nd street strip club in New York the previous December because he was underage. He didn’t want to go in anyway.

The magazine of Acceleration for the Eighties

This issue was an issue of firsts: It was the first to sport the favored byline (above) and the ubiquitous photo-collage of the Himalayan guy pulling a tugboat up a cliff, with a ThroTTle zeppelin drifting past in the background, both of which the magazine carried forth for many years. It was the first to have color, the first to contract out page layouts.

Issue #3 was also the first to officially break the magazine into sections, identified with section heads. The articles on the Village (by Rick Foster), Sears (Jerry Lewis) and the Prince in Williamsburg (by Janet Moore) fell under the head “ThroTTle / Facts”.

A fiction piece called “Mondo Limbo” (by Dale) and Mark Plymale’s piece on Janet Cooke fell under “ThroTTle / Lively Arts”

Ronnie Sampson turned in a wonderful piece called “international Style Dancing Lives Dimly” about George Stobie’s Topper and Tails School of Dancing at 200 N. 4th Street in Richmond, another in his series on Richmond’s marginal, fading and forgotten. Poems by George Williams, a striking drawing called “Stupid Dolls” by Lori Edmiston, followed by a fun page of censored art slides, a Phil Trumbo drawing, Dale’s TV listings and a Yellow Belly Jelly Beans ad (in honor of our new President’s favorite snack) rounded out the lively arts section.

This was the last issue of ThroTTle to be wholly financed by the staff (mostly Peter) and the last one to appear without advertising. As soon as issue #3 hit the streets (landing in all the favorite haunts) the staff hit the streets with issues and clipboards in hand, ready to start selling ads.

Hello sir [or ma’am], we are from ThroTTle magazine, a local arts magazine and we would like to invite you to become a part of our publication by considering purchasing an ad.

Beating the streets selling ads sucked, and nobody on the staff liked it. It was 100 degrees in June of 1981, a recession was on, and many small business owners either had no money for advertising or had their ad budgets tied up in local shoppers like Fan Advertiser and Fan Scan. But the ThroTTle staff knew that there was no way the magazine could continue without other sources of revenue.

Michael $ Fuller, former CT Editor and the first guy they knew to own a microwave oven joined the staff as Business Affairs Director and promptly set about ways to raise the needed revenue. Ad sizes were created and priced (a 1/8-page ad cost $25; a ¼-page ad cost $55; a ½-page ad cost $100 and a full-page cost $150). Contracts were created, and free layout and design services were offered for those who needed it. Mike was a no-nonsense business guy who bluntly said that the magazine could not last one more issue without an infusion of cash in one form or another. As major benefactors Peter and Bill agreed, and as the story ideas began pouring in after issue #3 the entire staff realized there was no way they could make a dent in the incredible volume of submissions and be fair in their presentation without a reasonable vehicle in which to place them.

ThroTTle was being forced to grow up and become a real presence in the arts community, whether the staff wanted it that way or not. There was no going back now – the only way to go was forward, and selling ads was going to be the way to get there.

Mike Fuller also forced the staff to look into the future and create 2- and 5-year plans, something the staff who were used to looking no further than the next issue had trouble doing. Where do you want to see ThroTTle in two years, he would ask. Would they be want the magazine to still be bi-monthly, monthly or even weekly by then? Would they want to be 24-, 48- or even 50+ pages every issue? Spot color or full-process color? Ok, then here is what you need to do now to get there then.

The biggest immediate problem the magazine faced was with the production equipment and facilities. The Commonwealth Times had been more than accommodating in letting the ThroTTle people come in and put together their issues in between issues of the CT, but that relationship was straining, and nearing a breaking point. Having almost unprecedented access to state of the art typesetting and camera facilities was a luxury the magazine was going to have a hard time giving up if the CT suddenly said “no more”, and that eventuality was going to have to be faced. Again, Mike, Peter and Bill were instrumental in setting the gears in motion in preparing a break from the CT should it occur. Luckily, the relationship continued through the end of 1981 and the emergency contingencies (involving IBM Selectric typewriters) were not needed.

Settling on a bi-monthly production schedule, the staff met numerous times to set deadline and production dates and streamline the production schedule so they did not have to give up all of their free time to put together the magazine. Bill Pahnelas was a wizard in setting the data entry and typesetting schedules so as not to conflict with the CT schedules. Dale was responsible for creating his own grid sheets and layout and production schedule so as not to “borrow” from the CT, who faced money problems of their own and would not tolerate supplies disappearing after every ThroTTle production week.

The work flow schedule was set in stone and followed rigorously. Arguments broke out regarding nitpicking Style usage, with one data entry person thumbing through an AP Style book to bolster her argument. This was serious business.

People showed up, wanting to work and not caring that they would not be paid one thin dime. “What do you need me to do”, they would ask. “Sell ads!” the Editors responded, but settled on giving them jobs typing, proofreading, setting up grid sheets, or distributing magazines when they came back from the printer.

Printing and distributing was another headache. The Ashland Herald-Progress had been very patient about printing the first three issues but decided after the third that they no longer could accommodate ThroTTle’s schedule. With only a handful of printing facilities available, Peter found Minor Armstrong at the Fredericksburg Free lance-Star, which turned into a God-send at the last minute. Minor, who was the production supervisor, was very patient and understanding dealing with the double- and triple-burns required by some of the screwier design aspects. A production and camera guy named Ralph ogled the accounting department women and trash-talked the management while he stripped the ThroTTle negatives, set the tabs in the goldenrod then burned the plates.

When the magazine started growing from 8 to 12 and 16 pages, and the press run was upped to 2,000+ it was decided that Peter’s green Valiant would no longer handle the press run, so a truck had to be rented from a guy named Herb Crumley at a rental place across the Nickel bridge on Forest Hill somewhere. Herb was also sympathetic to the plight of the Editors, cutting them a cut-rate price for a truck to bring back the papers in bundles and distribute them around Richmond. Once again, all this had to be paid by the benefactors (staff) out of their own pockets, making the necessity of ad sales even more critical.

Once a bi-monthly production schedule was agreed on, Production on issue #4 began, with ad sales being the first order of business. Dale and Bill teamed up and hit the Grace Street strip, going door-to-door with rate sheets and sample issues, introducing themselves and trying their best – with no ad sales experience – to talk the grumpy and hot business owners into buying ad space for the next issue.

They say you need 20 cold calls to land one sale, although in this case it was more like one out of 100. Like broken records, businesses lamented the same problems: “I don’t have any money”; “I have my ad budget tied up in one of the shoppers”; “I’ve seen your magazine and I think you suck”, etc. etc. Still, the boys persevered, and landed their first bonafide sale with A Sunny Day clothing and jewelry store at 410 N. Harrison, location today of the Village Restaurant, who bought a 1/8-page ad.

Peter, writer Jerry Lewis, text processor Peyton Whitacre and a couple others also pounded the pavement in late June / early July that summer, with a few striking paydirt, successfully selling a 1/8-page ad to the Outing Rental Center (possibly an easy sale since it was located right behind the ThroTTle office); a ¼-page to Liberty Tape at 824 West Broad and another 1/8-page ad to someone who was to become a most loyal supporters of the magazine – Benny Waldbauer, owner of the relatively new Benny’s at 611 West main Street, who in his ThroTTle-produced ad pitched shows by The Orthotonics, Bopcats and Dodge D’Art, as well as reminding readers that Monday and Tuesday were $2.00 pitchers, and Wednesdays were 50 cent bottles.

Even though the grand total of ads sold for that issue totaled 5/8 of a page and netted about $135, it was a colossal first step in the direction of financial independence for the magazine. To celebrate, the Editors decided to up the press run from 2 to 3,000 copies.

With Ad sales complete and slicks made up by the magazine’s “ad production staff” the editorial side of Volume 1, number 4 came together. Stories were typed, edited and proofread; artwork was assigned; photos collected and pages designed with a blueline pencil. More letters arrived and were published, including one that claimed the only thing worse than ThroTTle was a life-time subscription to The Watchtower.

“News” stories gathered under the “ThroTTle / Facts” section included another Sampson piece on McAlister C. Marshall, president of the Empire Monument Company in Richmond’s Oregon Hill. Peter Blake started what became a regular of reviews of other Richmond publications, starting in this issue with reviews of Charles Lohmann’s “The New Southern Literary Messenger” and the Tom Campagnoli / Amy Crehore glossy comics journal “Boys & Girls Grow Up”. Peter also wrote a piece on the re-opening of a “clean and sterile” Village café, claiming that instead of the grungy artsy hangout of yesterday it was now, in July 1981, “the kind of place a higher up in the state Republican party would want their college-age son or daughter to frequent.” Ouch.

Lori Edmiston contributed a piece entitled “Letter from Hawaii”, and Ron Smith got his first real assignment since his blistering letter in issue #3: a story about a KKK rally near Bowling Green, VA.

The centerspread – an interview with war hero and Alabama Senator Jeremiah Denton by D. Shone Kirkpatrick – appeared right after Ron Smith’s piece on the Klan rally and cemented ThroTTle’s success at venturing into hard-core politics. Denton gave very few interviews, so this was seen as a coup of sorts by the Editors. Local artistic genius David Powers provided his introductory illustration to the magazine.

The “ThroTTle / lively Arts” section featured an artistically sublime piece by Bill Pahnelas on a subject near and dear to his heart – Richmond’s Grace Street strip. Unable to reconcile the gentrification of the strip with the seedier aspects that it could not tear itself from, Bill lamented the slow yuppie creep in what he considered a personal territorial affront:

“The wooden plate was shut up. The Village was fading fast. Sonny and Buddy, young Achilles and his patrolcus, swaggered their finely shaped butts (in designer jeans only) where they could intimate their most personal desires. A few hard-looking boys in leather jackets hung around outside the now-defunct Sandy’s watching the preppie tide roll in, mammon’s minions.”

“And what of the winos who find their natural habitat on Grace Street?” Bill continued. “Are they an endangered species where fortune turns a favorable eye on the merchants of our beloved strip? Say yes and you smugly dismiss their human proclivity for adaptation. Say no and fork over 50 cents to the next wino you see. It is the contagion of slovenliness, a depletion of the human spirit, spent wads and dried-out orifices that brings them to the streets in search of Eucharistic joys, sacrificing the things of this world for the body and blood of their Lord, the grape.”

Artist and musician Rebby Sharp put in her own 2 cents on her experiences of living in a second-floor apartment on the same strip: “The sharpest contrast in activities is between the transient group of shells clutching the edge of sub-existence, asking for change and drinking it, and the group of ‘well-fed’, car-encased slopeheads out for their finely-honed idea of fun. . . The down-and-outers sitting on my doorstep are the first thing seen each day, and the rowdy hoo-hawers are the last thing heard each night.”

Following the artistic studies of Grace Street was a local music spread, featuring the first Rock and Roll column by Ron Smith and a piece on Richmond radio by Mark Plymale.

Page 14 was Dale’s Parody page, with a anal-obsessive ThroTTle Weather page (patterned after the Washington Post), and another entry in “ThroTTle / TV”. Gale Storm’s “Journey to the Center of Your Meat loaf” was on at 9 PM an channel 12. Chris Reed wrote “Barney Goes to Town” (about Don Knotts’ character Barney Fife, not the purple Dinosaur). The “ThroTTle / Last Blast” was another Jack Moore social satire featuring a talking monkey.

Blue happened to be the color on the Free Lance-Star presses that day, so Dale’s cover came off the presses as a bizarre 1950’s-style clip art collage highlighted in dark royal blue. Another happy accident.

Suburb-B-Q

To make issue #4 even more special, Ronnie Sampson and Nancy Martin came up with an idea to in their words “make ThroTTle more New Yorky”. Hand-stapled on page 3 in 1,000 of the 3,000 copies was a second publication – a photocopied 12-page 3”x4” fanzine called “Subur-B-Q Magazine”, featuring tiny illustrations and flash fiction by such varied stalwart Richmonders as Nancy, Lisa Austin, Jean Hollings and “Art Mutt”, in addition to some of the ThroTTle regulars, such as Dale, Bill, Jack and Ronnie. It was just another way to get more people involved in the excitement of publishing.

Staffers made a party of stapling the tiny magazines together and inserting them randomly back in the bundles of ThroTTles, but in the end it was considered too big a pain to do on a regular basis. Today, ThroTTle #4 with a complete issue of Subur-B-Q intact is quite rare.

The Staff of ThroTTle felt they had completed a major accomplishment with issue #4, and they congratulated themselves on the inclusion of a real second magazine, a real interview with a real U.S. Senator and real advertising in a magazine that started as an erstwhile one-shot whim less than 6 months previous. Mike Fuller was ecstatic as he deposited those checks totaling $135, and would not let one dime of it go for beer.

Although many did wonder how Mike paid for that microwave oven, prompting the nickname “MIKErowave Fuller”.

Coming next: How can Janet Peckinpaugh be intellectual property? Channel 8 tell’s ‘em how, then tries to put ThroTTle out of business.