“Q: What are the rewards of putting out a magazine like this since you don’t get paid or anything?

A: The rewards are more subtle than money. Perhaps the greatest reward is being in a position to decide what’s worthwhile and then sharing it with a wider group. It’s giving in a way that’s not obligatory. Determining what makes an [unsolicited] submission worth printing is the most rewarding challenge I can conceive. Maybe if we keep plugging away it will pay in a more material way.”

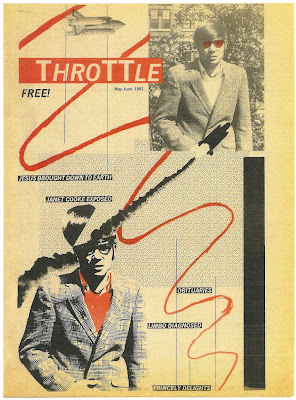

My name is Dale Brumfield, and I have been writing all the entries on this blog that you hopefully have been following this year, the 30th anniversary of “Richmond’s Better Magazine”, ThroTTle. I have intentionally switched to the first person for this final entry.

I have a theory that what truly makes a movie, a magazine, a piece of art or even a TV show memorable is not just the product itself but how well that product reflects the time period in which it appears, and how well it can continue to reflect the time period, even as the times shift and transition, without eventually appearing dated.

In July, 2010, I did a story for Style Weekly magazine (ThroTTle’s early nemesis) on a gentleman preacher who appeared on TV at 3 in the morning on the weekend in the 1970s and called himself The Circuit Rider. I was fortunate enough to interview his three sons at one of their south Richmond homes. One of the reasons for the enduring charm and relevance of the Circuit Rider (actual name Bill Livermon) is while his message is still relevant today, the manner in which he appeared on TV was perfectly suited to the time period, and that a similar “sermonette” would never make it in today’s TV programming. The Circuit Rider was filmed and edited by his wife, with a 16mm hand-held movie camera. They were only about 3 minutes in length, and were telecast anywhere between 2 AM and 3 AM on Sunday morning, just before channel 12 went off the air for the night.

Try getting a 3-minute fuzzy, 16mm film sermonette on TV today – especially complicated considering that TV no longer goes off the air anymore. But the Circuit Rider endures – a perfect example of how it exploited and reflected its time period.

I like to think that ThroTTle was equally suited to its time period, and did a good job not only reflecting 1980s Richmond but that it transitioned well and continued to reflect the local arts and culture scene as the eighties wore on. There was nothing else in Richmond at the time that was even close, so the environment was well-suited for a somewhat alternative, arts-based monthly tabloid. Yes, the magazine changed through the years, reflecting changes and turnovers in leadership and contributors, but the content drove the magazine, not the other way around, and that was the key to ThroTTle’s ability to show what Richmond was really about – not the Editor’s version of what it should be or what they wanted it to be. Every issue was a surprise to the reader, and that’s just the way we planned it.

At the end of 1981, when the magazine was on its way to being financially viable, and contributors were starting to line up to be a part of it, the founders – Peter Blake, Bill Pahnelas and myself – had no delusions of grandeur of the magazine. It was still considered alternative (a moniker I personally despised), a rag, an underground fanzine, etc., but we embraced all the descriptions of it, because as long as descriptions were being tossed around it just meant people were talking about us. Although we made the big jump in 1983 from bi-monthly to monthly, we never harbored any fantasies of becoming a weekly or a daily, nor did we actively seek out big money investors or buyers. We preferred to remain beholden to the community, not some faceless entity pulling strings behind a curtain. In other words, we would keep doing it as is until it became too big a pain in the rear. In doing so, in 4 years we went from debt to a $50,000 per year enterprise – in 1984 dollars.

A: The rewards are more subtle than money. Perhaps the greatest reward is being in a position to decide what’s worthwhile and then sharing it with a wider group. It’s giving in a way that’s not obligatory. Determining what makes an [unsolicited] submission worth printing is the most rewarding challenge I can conceive. Maybe if we keep plugging away it will pay in a more material way.”

-conversation between Bill and Peter; ThroTTle, January, 1984 issue

My name is Dale Brumfield, and I have been writing all the entries on this blog that you hopefully have been following this year, the 30th anniversary of “Richmond’s Better Magazine”, ThroTTle. I have intentionally switched to the first person for this final entry.

I have a theory that what truly makes a movie, a magazine, a piece of art or even a TV show memorable is not just the product itself but how well that product reflects the time period in which it appears, and how well it can continue to reflect the time period, even as the times shift and transition, without eventually appearing dated.

In July, 2010, I did a story for Style Weekly magazine (ThroTTle’s early nemesis) on a gentleman preacher who appeared on TV at 3 in the morning on the weekend in the 1970s and called himself The Circuit Rider. I was fortunate enough to interview his three sons at one of their south Richmond homes. One of the reasons for the enduring charm and relevance of the Circuit Rider (actual name Bill Livermon) is while his message is still relevant today, the manner in which he appeared on TV was perfectly suited to the time period, and that a similar “sermonette” would never make it in today’s TV programming. The Circuit Rider was filmed and edited by his wife, with a 16mm hand-held movie camera. They were only about 3 minutes in length, and were telecast anywhere between 2 AM and 3 AM on Sunday morning, just before channel 12 went off the air for the night.

Try getting a 3-minute fuzzy, 16mm film sermonette on TV today – especially complicated considering that TV no longer goes off the air anymore. But the Circuit Rider endures – a perfect example of how it exploited and reflected its time period.

I like to think that ThroTTle was equally suited to its time period, and did a good job not only reflecting 1980s Richmond but that it transitioned well and continued to reflect the local arts and culture scene as the eighties wore on. There was nothing else in Richmond at the time that was even close, so the environment was well-suited for a somewhat alternative, arts-based monthly tabloid. Yes, the magazine changed through the years, reflecting changes and turnovers in leadership and contributors, but the content drove the magazine, not the other way around, and that was the key to ThroTTle’s ability to show what Richmond was really about – not the Editor’s version of what it should be or what they wanted it to be. Every issue was a surprise to the reader, and that’s just the way we planned it.

At the end of 1981, when the magazine was on its way to being financially viable, and contributors were starting to line up to be a part of it, the founders – Peter Blake, Bill Pahnelas and myself – had no delusions of grandeur of the magazine. It was still considered alternative (a moniker I personally despised), a rag, an underground fanzine, etc., but we embraced all the descriptions of it, because as long as descriptions were being tossed around it just meant people were talking about us. Although we made the big jump in 1983 from bi-monthly to monthly, we never harbored any fantasies of becoming a weekly or a daily, nor did we actively seek out big money investors or buyers. We preferred to remain beholden to the community, not some faceless entity pulling strings behind a curtain. In other words, we would keep doing it as is until it became too big a pain in the rear. In doing so, in 4 years we went from debt to a $50,000 per year enterprise – in 1984 dollars.

|

| 6th Street Marketplace, "Richmond's proudest new erection". Click and look at it VERY close. |

Underground or above ground? Hipster or anti-hipster?

A recent Facebook discussion brought up the topic of whether ThroTTle was underground or aboveground, or whether it was hipster or anti-hipster. Personally, I maintain the magazine started out underground but sometime in 1982 or early 1983 it snuck aboveground, in a way none of us could have predicted.

Going “legit” can sometimes be traced to a specific event, article or issue. Rolling Stone magazine in the late 60s went aboveground over time because of a series of anti-Vietnam war articles. The evolution of advertisers represented on a magazine’s pages goes a long way toward legitimizing any publication; for example Creem Magazine in the early 70s became aboveground because its excellent music coverage drew big record advertisers. In fact, any hip publication that starts attracting big-name advertisers is going legit, whether they will admit to it or not. Attracting a big investor can have the same effect, and inevitably the content starts reflecting the publication’s newly-deputized financial status. It’s a tough road to hoe.

ThroTTle’s eventual trip up to the hallowed halls of aboveground publishing can be traced to a beer ad.

Brown Distributing signing on for a whole year of full-color, full back page ads transformed ThroTTle more than any one article or photo could have done. Because of the way the press was set up, a process-color back page paid for by somebody else meant we could also do a four-color process cover for no extra cost, and also include process color on the centerspread for very little cost. Suddenly a whole new world of cheaply produced dazzling covers opened up, and we quickly jumped on that opportunity, courtesy of Budweiser. The entire VCU arts community suddenly got out their oils, pastels and watercolors, and soon we had eye-catching and socially relevant works of art done by such local luminaries as Gerald Donato, Joe Seipel, Bill Nelson, Jim Bumgartner, and others that we may never had obtained before.

Suddenly everything changed. The beautiful color Budweiser ad on the back made people turn the magazine over to see what was on the front, then turn the page to see what was inside. Photographers started calling, even one AP photographer named Bob Strong who followed Jack Moore to a construction site to shoot the most artistic pictures of idle construction equipment we ever saw, free of charge. Philadelphia Enquirer Pulitzer prize winning Editorial cartoonist Tony Auth was more than happy to provide a perfect illustration for our article on the execution of Frank Coppola. Cartoonists from New Jersey and California (including SpongeBob artist Kaz and Matt Groening, who also did some cartoon I can’t recall) started sending strips. Writers and artists came from everywhere, and we were deluged with material and story ideas. Our press run changed almost monthly, going from 4,000 copies at the end of 1981 to 10,000 in early 1983 then topping off at 20,000 in 1985. We needed a bigger truck.

By 1983 we regretfully were having to say “no thanks” to more and more people, a process that must have driven Peter crazy, as it flew in the face of his original vision to let everybody be a part of the creative process. But, it was a sacrifice to growth, and hard decisions had to be made. We simply couldn’t afford a 50-page issue every month.

The beer ad spawned other big name advertisers with dollars to spend. Real Estate magnate David “your man in the fan” Peake, of Don Mann Realty, bought numerous full-page interior ads featuring head shots of himself. Numerous restaurants and music companies came on board, and of course the small “Band-Aid” ads grew in number to fill 2 and sometimes 3 pages.

Of course, local Movie mogul Ray Bentley never failed to reliably titillate and shock with his huge, garish 1- and sometimes 2-page midnight movie ads that were as much feature articles as they were advertisements. Ray was our first consistent full-page advertiser, and we still appreciate his unwavering support.

The four-color covers also created a dilemma of sorts: In those days a piece of color art had to be shot on a special camera that “separated” the art into four color negatives: red, yellow, blue and black. Those four negatives were then burned onto plates at the printer, and run on separate parts of the press to mesh the four colors together, re-creating the art on the newsprint. The problem was the four-color separation was prohibitively expensive. Although the Budweiser ads came already separated, we had to find a way to separate the cover art.

Bill Pahnelas found the solution. Utilizing a contact at a local printing press (that just so happened to print a local daily paper as well), an old-time pressman said he would be “happy” to shoot our artwork for us, free of charge. So once a month Bill snuck the artwork into the press room and this great old guy took an hour of company time to shoot and separate our next cover.

Our old Commonwealth Times friend Rob Sauder-Conrad took some time from founding Freedom House and protesting Ronald Reagan to scrounge some local dumpsters with me one Friday night to accumulate enough lumber to build hinged-lid layout tables (Binswanger Glass Co. had the best stuff in their dumpster), then – armed with an Apple IIe home computer that we bought for $3,800, and a dot matrix printer that cost another $600 in February, 1983 – we rented office space above the old Myers Jewelry store at 7 East Broad Street downtown (across from the Golden Steak Restaurant) and went to work in our brand new location.

This was actually our fourth location. After getting booted from the Commonwealth Times offices we put together three or four issues in Bill Pahnelas’ living room on Main Street before we set up shop in Michael Fuller’s basement on Sheppard Street. After about 4 months (and after Peter and I had the old woman next door pull a gun on us after overhearing an argument between her and her son) we got the space on Broad Street. Charles Lohmann graciously built us walls and doors, although we had no heat that first winter. A year later we were joined up there by channel 36 Coloradio (when it was absorbed by ThroTTle’s parent company), and the Neopolitan Gallery opened up downstairs.

Going “legit” can sometimes be traced to a specific event, article or issue. Rolling Stone magazine in the late 60s went aboveground over time because of a series of anti-Vietnam war articles. The evolution of advertisers represented on a magazine’s pages goes a long way toward legitimizing any publication; for example Creem Magazine in the early 70s became aboveground because its excellent music coverage drew big record advertisers. In fact, any hip publication that starts attracting big-name advertisers is going legit, whether they will admit to it or not. Attracting a big investor can have the same effect, and inevitably the content starts reflecting the publication’s newly-deputized financial status. It’s a tough road to hoe.

ThroTTle’s eventual trip up to the hallowed halls of aboveground publishing can be traced to a beer ad.

Brown Distributing signing on for a whole year of full-color, full back page ads transformed ThroTTle more than any one article or photo could have done. Because of the way the press was set up, a process-color back page paid for by somebody else meant we could also do a four-color process cover for no extra cost, and also include process color on the centerspread for very little cost. Suddenly a whole new world of cheaply produced dazzling covers opened up, and we quickly jumped on that opportunity, courtesy of Budweiser. The entire VCU arts community suddenly got out their oils, pastels and watercolors, and soon we had eye-catching and socially relevant works of art done by such local luminaries as Gerald Donato, Joe Seipel, Bill Nelson, Jim Bumgartner, and others that we may never had obtained before.

Suddenly everything changed. The beautiful color Budweiser ad on the back made people turn the magazine over to see what was on the front, then turn the page to see what was inside. Photographers started calling, even one AP photographer named Bob Strong who followed Jack Moore to a construction site to shoot the most artistic pictures of idle construction equipment we ever saw, free of charge. Philadelphia Enquirer Pulitzer prize winning Editorial cartoonist Tony Auth was more than happy to provide a perfect illustration for our article on the execution of Frank Coppola. Cartoonists from New Jersey and California (including SpongeBob artist Kaz and Matt Groening, who also did some cartoon I can’t recall) started sending strips. Writers and artists came from everywhere, and we were deluged with material and story ideas. Our press run changed almost monthly, going from 4,000 copies at the end of 1981 to 10,000 in early 1983 then topping off at 20,000 in 1985. We needed a bigger truck.

By 1983 we regretfully were having to say “no thanks” to more and more people, a process that must have driven Peter crazy, as it flew in the face of his original vision to let everybody be a part of the creative process. But, it was a sacrifice to growth, and hard decisions had to be made. We simply couldn’t afford a 50-page issue every month.

The beer ad spawned other big name advertisers with dollars to spend. Real Estate magnate David “your man in the fan” Peake, of Don Mann Realty, bought numerous full-page interior ads featuring head shots of himself. Numerous restaurants and music companies came on board, and of course the small “Band-Aid” ads grew in number to fill 2 and sometimes 3 pages.

Of course, local Movie mogul Ray Bentley never failed to reliably titillate and shock with his huge, garish 1- and sometimes 2-page midnight movie ads that were as much feature articles as they were advertisements. Ray was our first consistent full-page advertiser, and we still appreciate his unwavering support.

The four-color covers also created a dilemma of sorts: In those days a piece of color art had to be shot on a special camera that “separated” the art into four color negatives: red, yellow, blue and black. Those four negatives were then burned onto plates at the printer, and run on separate parts of the press to mesh the four colors together, re-creating the art on the newsprint. The problem was the four-color separation was prohibitively expensive. Although the Budweiser ads came already separated, we had to find a way to separate the cover art.

Bill Pahnelas found the solution. Utilizing a contact at a local printing press (that just so happened to print a local daily paper as well), an old-time pressman said he would be “happy” to shoot our artwork for us, free of charge. So once a month Bill snuck the artwork into the press room and this great old guy took an hour of company time to shoot and separate our next cover.

Our old Commonwealth Times friend Rob Sauder-Conrad took some time from founding Freedom House and protesting Ronald Reagan to scrounge some local dumpsters with me one Friday night to accumulate enough lumber to build hinged-lid layout tables (Binswanger Glass Co. had the best stuff in their dumpster), then – armed with an Apple IIe home computer that we bought for $3,800, and a dot matrix printer that cost another $600 in February, 1983 – we rented office space above the old Myers Jewelry store at 7 East Broad Street downtown (across from the Golden Steak Restaurant) and went to work in our brand new location.

This was actually our fourth location. After getting booted from the Commonwealth Times offices we put together three or four issues in Bill Pahnelas’ living room on Main Street before we set up shop in Michael Fuller’s basement on Sheppard Street. After about 4 months (and after Peter and I had the old woman next door pull a gun on us after overhearing an argument between her and her son) we got the space on Broad Street. Charles Lohmann graciously built us walls and doors, although we had no heat that first winter. A year later we were joined up there by channel 36 Coloradio (when it was absorbed by ThroTTle’s parent company), and the Neopolitan Gallery opened up downstairs.

Janet Peckinpaugh tells us to go to hell

In March, 1982 WXEX (now WRIC) channel 8 definitely saw us as underground – and apparently quite a threat. Their newly-hired news anchor Janet Peckinpaugh graced the final issue of Richmond Lifestyle magazine, and writer Genny Seneker decided to do a feature on the death of Richmond Lifestyle and the hiring of Ms. Peckinpaugh. A friendly request for a mug shot of Ms. Peckinpaugh resulted in a nasty mailgram from WXEX: “Strongly object to your proposed use of Janet Peckinpaugh’s picture in your magazine – letter to follow”.

Stunned by WXEX’s response, we then received a letter from Ms. Peckinpaugh herself: “After reading your letter and reviewing copies of your magazine, I am writing to inform you that you may not, under any circumstances, use my picture or name in connection with any story in ‘Throttle’. I would consider such actions slanderous, libel, and an invasion of privacy. . . Most of all, I fell that appearing in your magazine would be detrimental to me as a professional journalist.”

Wow – we had no idea we shaped public opinion that adversely. And for a “professional journalist” as she claims, she should have known exactly what libel entailed.

|

| The Peckinpaugh correspondence. Click to read. |

More letters followed, both from the WXEX station manager and from the station’s law firm, May, Miller and Parsons: “we must advise you that an invasion of the rights and/or privileges of Ms. Janet Peckinpaugh or Nationwide Communications, Inc. by the ‘Throttle’ or any person or persons associated or producing or printing or participating in the invasion of either of our clients’ rights will be looked to for full and complete compensatory and/or punitive damages.” Signed very truly yours, G. Kenneth Miller, for the firm.

It seems odd that a public persona and a public broadcasting entity would be so protective of their “property” that they would go to these lengths. ThroTTle responded as we knew best – by documenting the entire sordid affair on page 3 of the March, 1982 issue, complete with a wonderful Greg Harrison illustration of Janet Peckinpaugh punked out in spiked hair and leather jacket. We mailed copies to everybody. But the matter died, as did WXEX’s ratings after hiring Ms. Peckinpaugh. 15 years later ThroTTle was still around, and Janet Peckinpaugh was but a distant Richmond memory.

Read this article about her to see how thing are going for her now up in Connecticut.

Whether the Peckinpaugh episode had anything to do with it, content as well as advertising rolled in, and we had to reorganize our staff to handle the influx of material arriving on a daily basis. Instead of the title Art Director I became Production Manager, and hired an Advertising production manager (in charge of producing the ads). Michael Clautice did a superior job of organizing the ads for the next issue, and gave us long expositions of his methods that included a rapidograph pen and an accordion file. Long-time contributor Kelly Alder took over as our first Art Director to assign illustrative art assignments. Beth Horsley became Chief Photographer and Doug Dobey was hired as Comics Editor. In News, Arts and editorial we created News Editors, Arts Editors, Associate News Editors, Calendar Editors, and a plethora of associates, proofreaders and data entry operators. It was thrilling to see people bustling around, doing their respective jobs, arguing what needed to be argued and respecting the copy flow and production process we created to ensure the smooth operation of the next issue. Some could argue we were still underground, but our streamlined processes were definitely aboveground, and rivaled any other “legit” magazine anywhere.

Very little changed in the actual mechanics of production, although we crowed about our cutting edge technology when we bought the Apple computer. The Apple came equipped with a mono monitor, a CPU, and a systems disk and several document disks. Also included was a gizmo called a modem, which allowed us to transmit our issue text to William Byrd Press at a blazing 2.4 KPS on Sunday night, then Byrd would print out the galleys, run them through a waxer at no extra charge and deliver them back to 7 East Broad on Monday afternoon. The down side? The production people had to learn to “spec” type to make it all fit, although I tried to make things easier by dummying out the entire issue with a blue line pencil to show where everything went. After that it was like paint by numbers, and it always seemed to fit. We were the wave of the future.

Then, in November, 1982, we got competition. A magazine called “Style” suddenly showed up in apartment building foyers all over Richmond. We didn’t consider it authentic competition, since they obviously were going after another readership demographic with stories about the “Friendly Frosters Cake Decorators Club” (not a joke), but we did not take Style lightly.

We happily announced the Appearance of Style (“How do you publish while eating a croissant?”, Nov. 1982 issue) but the fact is, after a year or so we became a major pain in the ass to them. We discovered the identities of not one but two of their anonymous restaurant reviewers, George Stoddart then Christian Gehmann, revealing them complete with photos. We delighted in lampooning their “tea and crumpets” attitude, but the kicker was when Bill and I dressed up like homeless men (not a real stretch for either of us), got a shopping cart and spent a couple Friday evenings rifling through Style’s trash in the alley behind their Franklin Street office under the guise of looking for aluminum cans. We found hilarious in-house memos, notes, story ideas and other detritus, then either published them as is or referenced them in our content (one particularly funny note from editor Lorna Wyckoff to someone named “Conrad” extolled the virtues of hiring Baylies Willey – “an old Hollins chum” – as their Marketing Rep. The note ended “. . .Toodles, Lorna”).

At one point Ms. Wyckoff allegedly called a lunch meeting with VCU Mass Comm Professor George Crutchfield to see if there was anything anyone could do about ThroTTle. Little did she or Crutchfield know but that their server that day was a ThroTTle contributor, and overheard everything they said, relaying it back to us.

After a while, however, we got tired of hounding Style, and just left them alone. Happily, Style is still published as a weekly, and I proudly count myself as a regular contributor. And, Lorna Wyckoff is a Facebook friend. No hard feelings?

One day these punk kids showed up.

Shortly after moving into 7 East, Peter announced at one of our weekly staff meetings that we had just started an internship with Open High School. Seriously, he said, these kids would get high school credit for working at ThroTTle. I shrugged – “another one of Peter’s schemes” I thought, but it became apparent pretty quick that these three punk kids had a legitimate role to play and seemed sincere about doing it. One in particular – this wise-cracking chick in denim coveralls who at age 15 professed to sending correspondence to Ted Bundy and gave most of us this quizzical, disbelieving look whenever we asked her something, quickly assimilated and proved herself to be an excellent writer and diehard worker. Anne, or “Timmie” as she was called, wrote with the maturity and wizened sarcasm of someone twice her age. Timmie stuck with us for a couple of years, before graduating and going off to William and Mary, where she was quick to point out via post card any mistakes we made. Timmie – or as she is known today as Anne Thomas Soffee – is an accomplished writer for Richmond magazine and the author of a couple of books. We are proud to counter her among our staffers. Of course, all of our other interns in those years – Wade, Michelle, Mark, Mary and others – played crucial non-writing roles in such areas where we lacked manpower, such as in data entry, subscriptions and distribution.

Anne was one in a long line of incredibly talented and hard-working writers that took their assignments seriously, even though they would not get paid one dime for their work (Anne and Andy Marcus scored an interview with Black Flag lead Henry Rollins for the 9/85 issue). Donald Wilson showed up and handed in a terrific piece on local poet Rik Davis, who had been murdered in 1981 at his job at an adult bookstore – a murder that remains unsolved in 2011.

Other literary and musical interview highlights of the 80’s include:

- An interview with fiction writer William Crawford Woods, by Michael Stephens in July, 1982.

- Lori Edmiston interviewing Waverly, VA folk artist Miles Carpenter and also the Orthotonics, May, 1982.

- a terrific interview with organist Eddie Weaver by Mark Mumford in the April, 1983 issue.

- Kelly Alder and Sparky Otte scored an interview with the Rockats in the Much More dressing room (Much More was a club on Broad Street).

- Bob Lewis’s interview with illustrator Berni Wrightson was one of the only interviews Wrightson did in the 80’s.

- Donna Parker did a rather unforgettable interview with Dream Syndicate in July, 1983.

- Trent Nicholas contributed numerous film commentary and reviews, including “Liquid Sky” and “Futuropolis”.

- John Williamson wrote two great pieces in the January, 1983 issue – one on the Bad Brains and the other was an interview with Richard Hell (of Richard Hell and the Voidoids).

- In the September, 1983 issue, Tom Wotherspoon snagged an interview with singer Grace Jones, Bill Pahnelas interviewed the Ramones and Lori Edmiston had an excellent piece on REM.

- The June, 1985 “Interview” issue had interviews with Times-Dispatch film critic Carole Kass, attorney Mary B. Cox, director John Waters, Cartoonist Colleen Doran, Dika Newlin and Tiny Tim.

- An interview with and story about primitive artist Howard Finster, by Clair Frederick, April, 1986.

- And of course, that is a woefully inadequate sampling. There were tons more.

|

| David Powers feature, 1983. Deliciously unexplainable. |

On October 26, 1983, the office was broken into and heavily damaged. Tables were turned over, art supplies were thrown everywhere, our $600 printer was thrown into a light box, demolishing them both. And, best of all, the culprit(s) took a dump on the floor and smeared it around. Thankfully the computer was left alone, or we would have been out of business. It took days to get back to normal, and the guilty were never found. Dirtbags.

One day Bill came up to the office after a particularly bad day at work and just paced the floor, doing nothing and arguing about everything. When he finally stormed out and went home because I had neglected to bring beer with me, Peter looked up from the computer and said, “I wanted to punch him, but I was afraid he would fly into a frenzy and kill me.” The pressure was starting to build.

Ned Scott was a welcome addition to the staff, but somehow seemed to find his way into the middle of any controversy that arose. An Al Pacino lookalike in black hi-top sneakers, with a penchant for bumming a cigarette then breaking off the filter before lighting, Ned succeeded in endearing himself to half the staff and severely pissing off the remainder. He was aggressive, loud and demanding, but he wrote excellent pieces, which ultimately was seen by the reader without knowing the sometimes histrionics behind it. “Ned provides local color” someone remarked.

Press day was always the source of a lot of wailing and teeth-gnashing. I hated press day. The night before (usually around 1 AM), after all the maddening details were corrected and the page numbers, footers, taglines and cutlines were in place, and after the pages had been rolled and washed down with Webril wipes soaked in Bestine, the “flats” were put to bed in a box. Bill and I then arose at 6 AM and drove the flats to Fredericksburg to the Free lance-Star building. After dropping off the flats we got our trash-can size 7-Eleven coffee and went back to watch a production guy named Ralph strip our negatives and burn our plates while he bitched and moaned about his job and retirement and ogled the pretty girls in the news room. Once the press was plated and started, a few copies slowly emerged, which we scooped up and rifled through to make sure there were no major errors. Once getting our thumbs-up, the press went into high-speed production after minor adjustments were made, and after about 2 hours we were loaded down with 20,000 printed and bundled copies of ThroTTle heading south on I-95. And it never, ever looked as good as I thought it should. Printing was anti-climactic after living with it for over a month, and I was already looking forward to the next one.

Once back in Richmond we picked up Peter and delivered several thousand around town before calling it a night. Once I sideswiped a car on Strawberry Street with the delivery truck. Another time Bill told a group of guys in a car on Grace Street that he didn’t have to move the truck, because it was a “Bonafied delivery ve-hicle, so F*** YOU!!”, causing me to drop down out of sight so any bullets coming through the side window would miss me and hit him. After a second accident our rental company suddenly no longer had any vehicles available for us anymore. It was an exhausting 14-hour day at the end of an exhausting month.

In late 1983 we incorporated the magazine under a sub-chapter S company called “Acceleration for the Eighties, Inc”. We issued stock on 1/1/84 worth a dollar a share to the three founders and Mike Fuller, our Business Affairs Director. We had a bank account and a loan that we all signed for to buy the Apple IIe PC. We acquired Channel 36 Coloradio, and they moved their broadcasting operation to 7 East. If we weren’t aboveground before, we certainly were now.

In November, 1985 Peter abruptly stepped down as senior Editor, following Bill who had to step down earlier that year due to a no-compete clause with his job at the Richmond News-Leader. Peter stayed on in more minor capacities, but he was burned out – as was I, but felt compelled to keep going. Jeff Lindholm stepped in as co-senior editor, but By February, 1986 ad sales had plummeted due to sales manager Michael Woodall’s flaming out as well. Despite the excitement of moving into swanky new offices in St. Alban’s on Main Street downtown, the fire went out. People were finding reasons not to keep busting their butts for free – go figure. Quality stories were getting harder to come by. I tried my hand at another Albrecht Durer-style cover (“The Resurrection of St. Elvis”) on the April issue, but by August of that year even I was done. The strain of volunteering all my time for almost 6 years on a monthly magazine has worn me completely out.

Then, salvation appeared as Ned Scott Jr. Ned said he wanted to take over the magazine, build a whole new staff, re-design it and basically start all over with a fresh new focus. This was a no-brainer to the rest of us – we convened a meeting of the board of directors and unanimously voted to turn the magazine and control of the board over to Ned. Of course a screaming match started over something, but the change was complete and we celebrated with Black labels.

It was a good thing I got out when I did; I look back at the last couple of issues I was involved with and my bad attitude is all over them.

In January, 1987, I married my wife Susan and the first issue of the new ThroTTle appeared. It was a damn good issue – a robust 16 pages, highlighting the AIDS epidemic. Yes, 16 pages was down from our high of 40 pages in early 1984, but the magazine was at least now off life support. Ned had done a great job creating a new staff, with new writers and editors. Doug Dobey redesigned the magazine, and it had beefier arts and sports coverage. Brown Distributing was back on the back page again. It was a wonderful start under dire circumstances.

Once Peter, Mike, Jeff Lindholm and myself turned the magazine over to Ned Scott in late November, 1986 I walked away and never looked back. I continued to pick up the issues when I saw them but I even stopped doing that after a while. That part of my life was over, and I flipped that switch off.

What is so weird is that even today I periodically bump into people who tell me that they wrote for ThroTTle, or had a drawing published, and I have no idea who they are. I currently have a short story published in an anthology called “Richmond Macabre”, and one of the editors, Phil Ford, informed me that he was a contributor to ThroTTle “in the 90’s”. It is a very gratifying but alien feeling to meet someone who helped keep a magazine going almost 19 years after I helped start it, and an unspoken kinship still seems to exist between the 1980s staff and the 1990s staff.

I am asked periodically if a magazine like ThroTTle could make it today. Regretfully, I don’t think any magazine can make it today existing the way we did, especially. Overhead costs a fortune, and good luck finding volunteers willing to keep it up over the long haul. Ad money can only bring in but so much, and you are beholden to everyone when you are so dependent on their ongoing revenues and not on a silent sugar daddy. If you piss off a major advertiser and lose them, it is financially crippling, and very difficult to recover.

Any arts and culture magazine thinking of making a go in this climate has to have a very robust web presence, and be very innovative in how it meshes its online presence with its hard copy sister sitting in bundles in the bookstores, apartment foyers and dentist offices. I don’t have that answer, and shudder to think of the work involved in starting something from scratch all over again. Then again, if any of you reading this decide to take a crack at it, help yourself. Just please don’t call it ThroTTle.

My hat is off to Ned (thanks for taking over), Dorothy Gardner (ditto), Ann Henderson (ditto again), Mary Blanchard (final ditto) and all the others who labored to keep the magazine going in one form or another from 1981 to 1986, then ultimately until 1999, especially Doug (always perfection), Kelly (Mr. dependable), Linnea (great delivery), Michael (great ads, but enough with the accordion file already), Bud (the jolly Russian shot-putter), Dabrina (damn fine editing), Don (I’ll show ‘em, honey), Frank (we sang along with you often), Margaret (always had coffee ready), David (the Valentine issue cover is a classic), Lori (A great artist, and just a pleasure to have around, even though we argued constantly), Shade (the most strange one of all), Brooke (you made a good Russian security cop), Mark (did you take Peter’s bicycle?), Genny (don’t worry, Janet Peckinpaugh is not coming after you), Timmi (snark snark), F.T. (great job getting the VCU professors on board), Jack (stop throwing chairs), Don B. (the reincarnation of Thimble Theater), Pam (unforgettable 80s hair), David (great pictures), Phil (show me your Emmy – and where’s my dang glue gun?), Caryl (best toothbrush collection in town), Kaz (best of luck on SpongeBob), Sheldon (I appreciated your phone call that time), Wade (are the issues out yet?), Sue (wild turkey), Maynard (I never even met you but I hear you delivered our magazines in Charlottesville) and everybody else, especially Simpsons creator Matt Groening (I’m sorry I turned down your comic “Life in Hell”, but it was so stupid).

I discovered that if I took all the articles I wrote on this blog and put them in a book it would be 76 pages, not including art. Perhaps some of the 1990s people would like to step up and write a history of their years with the magazine. We would have a true library-quality item at that point. Any takers? Ann? Mary?

Thanks also to everyone too who picked up and read ThroTTle from those early years. Thanks for patronizing the advertisers, and thanks for the good word of mouth. It meant a lot.

I’m putting this blog to bed.

Good night, and God bless,

|

| (1981 Woolworth photobooth) |